Deathbed Ramblings of Islamized Armenian Orphan to Granddaughter: ‘We ran from the Kurds and soldiers’

In a weird twist of fate, it was the onset of Alzheimer’s that got Mrs. Ogyut, well past ninety, to recount fragments of her Armenian childhood; something she never mentioned to her family.

Slipping in and out of consciousness, Mrs. Ogyut repeatedly recounted one particular image from her lost childhood.

“They were in a tunnel and fleeing from the Kurds and soldiers who were firing at them. They were killing the parents,” Evrim Hikmet, the granddaughter of Mrs. Ogyut tells Hetq. “The she cries and the soldiers, hearing her cries, come and take her.”

This is the story that Mrs. Ogyut recounted before she died. She would also wake up and say that she saw her mother’s silhouette on the window.

Mrs. Ogyut was raised by a wealthy Turkish family in Nishan Tash, the most fashionable neighborhoods of Istanbul.

She never went to school or learnt to read and write. She was married off to a lowly servant who, according to the granddaughter, was also illiterate.

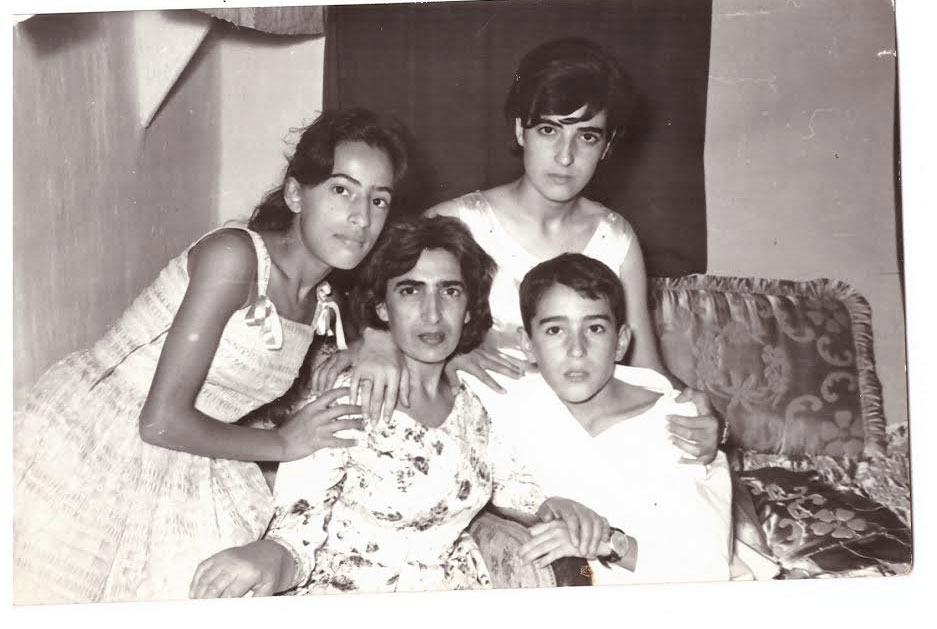

Evrim says that her family reckoned grandma was adopted by this family but thought that they just didn’t treat the orphan correctly. Mrs. Ogyut had three children; one was Evrim’s mother.

The issue of my grandma’s illiteracy and that she was married to someone outside the family circle always raised questions for us,” says Evrim. “I know that my grandmother didn’t wish to marry my grandfather because she never met him before the marriage.”

The names of Mrs. Ogyut’s parents – Fatimah and Abdullah - in her passport, also is proof that she was an orphan. Evrim says it’s a known fact that these were the names used during the early years of the Turkish Republic and Ottoman Empire, when the names of a child’s parents weren’t known.

“You can even see this is the case by watching today’s Turkish TV soap operas,” Evrim says.

Mrs. Ogyut was one of Armenian orphans of the Genocide who were taken and given to the care of Turkish families. Another bit of evidence to back this up is the fact that her mother was born in Erzeroum. However, Mrs. Ogyut’s passport states that she was born in Manisa, a large town near Izmir. Evrim confesses that the family lacks any credible information regarding where Mrs. Ogyut was born.

Evrim says that the ramblings of her grandmother were taken as credible because when she recounted the episode of fleeing the soldiers in the tunnel, the old woman said they fired at her feet. It turns out that the woman had a deep scar on one of her heels. She also harbored a hatred for the Kurds all her life.

“When I was a child and asked her about the wound, she would say that someone fired a gun at her foot whole playing a game. She never remembered the details,” says Evrim.

Throughout her life, Mrs. Ogyut also talked about the gold and silver items she once owned but which were seized by her aunt’s family.

An interesting aspect of her life is that Mrs. Ogyut traveled to Japan with a cousin of her adopted family who was an opera singer. She spent five years in Japan and learnt the language.

Evrim says that they have no dealings with the family that adopted her grandmother. She adds, however, that her mother told her that when she was twenty or so the opera singer once visited them and that an argument broke out between her grandma and the singer.

“After the singer left they never saw each other again. My mom couldn’t understand anything because they were taking Japanese,” says Evrim.

Evrim says that her mother wanted to find out more about that wealthy family but was unable to. The family broke all ties with their adopted girl after she got married. Evrim says they know that the family still lives in Istanbul and owns a number of businesses, including hospitals.

Thus ends Evrim’s story about her Armenian roots - a story that has gotten her family to think about their own identity.

“When I told my brother the story he joked saying last year I was a Turk and this year, an Armenian,” Evrim says. “However we never thought she wasn’t a Turk until she fell ill.”

Estimates say 63,000 Armenian orphans shared the fate of Mrs. Ogyut. This is the conclusion of Turkologist Ruben Melkonyan who cites this number in a 1921 report prepared by the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople. It corresponds to the number that appears in an August 30, 1921 report presented to the League of Nations, according to which 90,819 Armenian children and woman were freed from Muslim households but that an equal number remains in Muslim families.

Evrim says that she isn’t looking for information about her grandmother’s past and that it isn’t important whether she has Armenian, Turkish or other roots. What is important is to know about diversity because being different, in a country like Turkey, is par for the course.

“All of us have built this country together. And it’s normal to have different roots in a country like this. What’s bad is that we have been forced to neglect that diversity an only know about the Turkish side,” says Evrim.

She says that her family has lived as a Turkish family, which in Turkey is an advantage. She adds that while not being nationalistic, her family has, in essence, benefited from this advantage.

“But that advantage has derived from tragic events and we have enjoyed that advantage without knowing that it’s built on the sorrow of others,” she says.

Evrim is a musicologist and teaches music at Istanbul’s Mimar Sinan University. Currently, she’s researching the music of Iraqi migrants.

She grew up in the Istanbul neighborhood of Beşiktaş, where calling anyone Armenian was considered a slur, an outcast.

“I now believe it was all a lie. It not only refers to my family but to any others, and we are all living in that denial,” Evrim says. “I believe that we must first be open about this and discuss it publicly in order to know our roots and past.”

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Comments (5)

Write a comment